“All the wrong people remember Vietnam. I think all the people who remember it should forget it, and all the people who forgot it should remember it.”

Color me gone

There was a map of Vietnam on the wall of my apartment in Saigon. But unlike the French Indochina map of American author Michael Herr in the beginning of Dispatches, my map was a modern-day, colorful enigma tempting discovery and adventure. During the ten years I photographed Vietnam, this map was eventually replaced with Google Maps on my phone where I could literally record my every movement throughout the country.

I was born four years after the Fall of Saigon and as a white American, I inherited the guilt, the failure, all the remnants of what we call the Vietnam War. Just as I have been an active participant in remembering of all the wars fought since, I am complicit in perpetuating the post-war perception of Vietnam. Over the years, most of the memories I have encountered have been collectively manufactured by White America. Vietnamese-American author Viet Thanh Nguyen eloquently describes this in his book Nothing Ever Dies as an industry of memory that is controlled by the superpowers. Their power to “disremember” through mass media changes our perception of history over time. He writes, “Globally, the American industry of memory wins. People the world over may know the Vietnamese won the war, but they are exposed to the texture of the American memory and loss via projected American memories.”

It wasn’t until I befriended a Vietnamese-American refugee family while working in California that I began to learn about less popular memories. Their nostalgia both intrigued and troubled me. As we became closer, I felt the need for a deeper understanding of why their memories were so different to what I knew. I first discovered Vietnam biased by those appropriated memories. While tourists littered the coastline taking selfies in conical hats, I sought to contrast a time that was long past.

I didn’t want to create a book about war. But at the same time there is no possible way to talk about our perceptions of Vietnam without acknowledging how we got there. What I found was a complicated country that suffers from its own kind of amnesia. What Vietnam calls the American War has shaped everything they have created since.

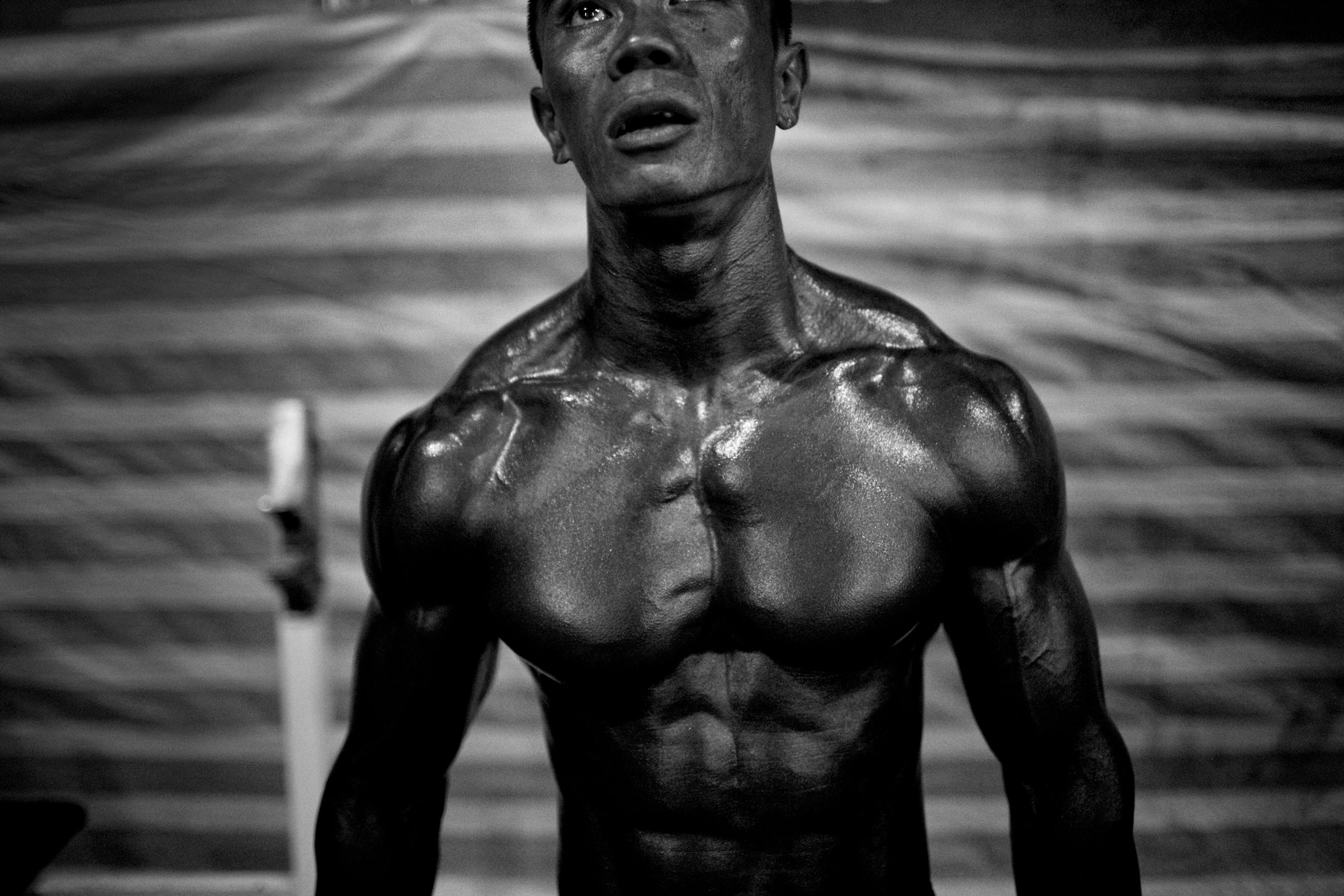

I sometimes felt like an uncomfortable witness to Vietnam’s growth. Toeing the line between my loyalty to those who fled the country and my fascination with the architects who are designing a new Vietnam. But over time, the new Vietnam became less of a place and more of an idea. A veiled capitalist dystopia constantly moving forward to the detriment of everything left behind.

While Herr helped to fuel the American industry of memory by co-writing films like Apocalypse Now and Full Metal Jacket, it’s a quote that he said two years after Kubrick’s film was released that resonates most. “All the wrong people remember Vietnam. I think all the people who remember it should forget it, and all the people who forgot it should remember it.”

The power of this statement lies in the perception of the reader. Whether we are victims or victimizers, or the descendants of both, Nguyen argues that we are all complicit in playing a role in the ethics of remembering.

Make no mistake, this book is my biased journey of discovering memories other than my own. It is a book that documents a rapidly developing Vietnam in spite of its post-war ghosts. It slowly became contrasted with a kind of film noir where I romanticized a nostalgia that I never knew. It is both a love letter and a signed confession. The love and frustration I feel for Vietnam is not unlike that of my own family.

The answers to which I once sought were inevitably met with more questions. Some of the subjects in these photographs will surely become life-long friends, while others are already fading memories. Their experiences, which were undoubtedly different than mine, led me to question my own perceptions. Ultimately Vietnam will continue to mean very different things to different people. The memories of those affected the most are fading now. How we choose to continue their stories will echo into the future